COYLE, Mary (ca 1814 – 1846)

Biography

Mary Coyle was born in Ireland around 1814, the daughter of Peter Coyle and Mary Brennan. At some point, she emigrated from Ireland to Quebec.

From 1830 onwards, Coyle was imprisoned over and over again in the Quebec common gaol – almost 80 times between 1830 and 1846, for periods ranging from eight days to two months. She was almost always accused of being “loose, idle and disorderly”, a catch-all offence which covered a wide range of undesirable behaviours, from vagrancy to prostitution. Middle-class morality in the nineteenth century was less and less tolerant of women such as Coyle who did not conform to feminine ideals. In all, she spent over half of her life in prison between 1830 and 1846.

Coyle was part of a small group of “disorderly” women, mainly of Irish origin, often prostitutes, who made up a large proportion of the female prisoners in the Quebec common gaol. In 1829, a separate building was set aside as a women’s prison. The prison was much more than just a place of punishment. It also served as a refuge in a city where there were few resources available for poor, “immoral” women, especially during the long, cold winters. There were even many women who asked to be locked up in prison, by voluntarily confessing to being “loose, idle and disorderly”. This was better than dying outside. In prison, most of these women, like Coyle, were put to hard labour. This was less rigorous than one might think: for women, it meant a few hours a day sewing, or picking apart a limited quantity of oakum (old hemp ropes, used to make caulking for ships).

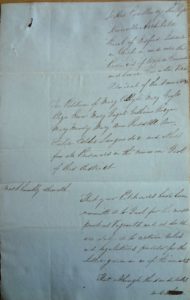

Coyle briefly stepped out of anonymity in 1837, when she was one of a group of women who signed a petition against the matron of the women’s prison, Elizabeth Cooke and her husband, Thomas. The petition, sent to the colony’s governor, Lord Gosford, accused the Cookes of a series of misdeeds. Among others, the petitioners accused the Cookes of imposing arbitrary punishments on them and of illegally selling them provisions, at inflated prices. They also claimed that the Cookes were drunkards who constantly fought each other, to the point that it was the prisoners who had to separate them. The petition was a good example of how women prisoners were willing to resist an administration which did not correctly manage “their” prison. Such resistance, however, had serious limits. Gosford ordered an investigation by the sheriff, William Smith Sewell (who was responsible for the prison). Sewell’s report cleared the Cookes of any wrongdoing, and though Thomas left the institution soon afterwards, Elizabeth stayed on as matron until 1840. As for Mary Coyle, she went back to the usual routine of incarceration, release, and incarceration again.

This hard life eventually killed Mary Coyle. She died at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Quebec City on April 8, 1846, aged 32. She had been imprisoned for the last time on March 16, at her own request, for two months at hard labour. The prison register does not show when she was transferred to the Hôtel-Dieu, but she evidently became ill while she was in prison (though not necessarily because of conditions in the prison itself). Although the women’s prison was a refuge, it was far from an ideal one for women like Mary Coyle.

– Donald Fyson, June 2015

Images

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, «Le fichier des prisonniers des prisons de Québec au 19e siècle», <http://www.banq.qc.ca/archives/genealogie_histoire_familiale/ressources/bd/instr_prisons/prisonniers/index.html> (transcription of the Quebec common gaol registers, the originals of which are in Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, Centre de Québec, E17,S1).

- Library and Archives Canada RG4 A1 vol. 508 file 1837-04

Secondary sources

- Fyson, Donald. “Prison Reform and Prison Society: The Quebec Gaol, 1812-1867”. In Louisa Blair, Patrick Donovan and Donald Fyson, From Iron Bars to Bookshelves: A History of the Morrin Centre (Montreal: Baraka Books, forthcoming).