JOHNSON, Susannah Willard (1730 – 1810)

Biography

Susannah Johnson (née Willard) was born in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, February 20, 1730, the daughter of Moses Willard Sr. and Susanna Hastings. Her ancestors were part of the elite of early Puritan settlers in New England. On June 15, 1747, she married James Johnson in Lunenburg, Massachusetts; the couple had seven children.

Like many American colonists, Johnson’s life was caught up in the imperial rivalries that shook the continent. In 1749, she settled with her husband at Charlestown (Fort No. 4), New Hampshire. On August 30, 1754, Johnson, her husband James, her son Sylvanus, her two daughters Susanna and Polly, her sister and two neighbours were abducted by an Abenaki raiding party. It was barely three months after the beginning of the conflict that would later become the Seven Years War in Europe. Johnson was pregnant, and the next day, on the trail, she gave birth to a daughter whom she named Captive.

The prisoners were taken to the Abenaki village of Saint-François-du-Lac. The Johnson family was then separated. James and the two eldest daughters were sent to Montreal to be ransomed, a common practice. Sylvanus was adopted by an Abenaki family, who soon left on a long hunting trip. Captive and Susannah were also adopted, by the Gill family, but then brought to Montreal in November and ransomed to the merchant René de Couagne, who in turn hoped to recoup his investment from the Johnsons. The Johnsons were at first well-received by Montreal’s high society. James was even allowed to travel to Massachusetts to raise funds to repay de Couagne and free his family. But in July 1755, after returning empty-handed, James was imprisoned after a dispute with de Couagne and La Corne Saint-Luc, a Canadian officer. Soon thereafter, all save Susanna (Susannah’s eldest daughter) were sent down-river to be imprisoned in Quebec City.

In Quebec City, Susannah Johnson and what remained of her family were locked up in the prison next to the Intendant’s Palace. They were first in the criminal section of the prison, in very grim conditions; they were then transferred to better lodgings in the civil section, with access to the prison yard and permission to make trips into town to buy provisions.

In autumn 1757, after more than two years in prison, the remaining Johnsons, other than James, were released during a prisoner exchange. They were sent to England, but then returned to North America to be reunited with James, who had himself since been released.

The Johnson family was deeply affected by their ordeal and by the war in general. James died in July 1758 during the Battle of Ticonderoga. Sylvanus remained with his adoptive Abenaki family until the autumn of 1759; on his return, he no longer spoke English. Finally, Susanna, the eldest daughter, remained in Montreal, in a Canadian Catholic family, until September 1760; on her return, she spoke only French.

Susannah returned to New Hampshire. In 1762, she married her second husband, John Hastings Jr., with whom she also had seven children. She died on November 27, 1810, in Langdon, New Hampshire.

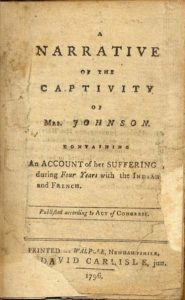

Four decades after her ordeal, towards the end of her life, Johnson set about recording the story of her captivity. Her tale was published in 1796, as A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Johnson Containing An Account of Her Sufferings During Four Years, with the Indians and French. Although the text has often been attributed to Johnson alone, the main author was actually lawyer John Curtis Chamberlain, though Johnson was also heavily involved. The book was part of what was then a popular genre, the captivity narrative. It differed from other similar works in that it avoided sensationalism, while at the same time having a decidedly political bent, with strong criticism of the two imperial powers. Johnson also painted a sympathetic portrait of the culture of her Abenaki captors, and condemned the conduct of the French authorities and of Canadians such as La Corne, held responsible for her family’s long imprisonment. The book was a success, and the story of “Mrs Johnson” was republished nine times during the next half-century. The most comprehensive and reliable edition is that of 1807, the last to which Johnson herself contributed. Johnson’s book was her lasting legacy, and still provides valuable information to scholars on the experiences of American prisoners of war among the Native allies of the French and in pre-Conquest Canada.

– Donald Fyson, June 2015

Images

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Johnson (Mrs). A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Johnson Containing An Account of Her Sufferings During Four Years, with the Indians and French. 2nd ed. Windsor: Alden Spooner, 1807. <https://archive.org/details/cihm_41351>

Secondary sources

- Carroll, Lorrayne. “‘Affecting History’: Impersonating Women in the Early Republic”. Early American Literature 39(3)(2004): 511-552.

- Fyson, Donald. “Prison Reform and Prison Society: The Quebec Gaol, 1812-1867”. In Louisa Blair, Patrick Donovan and Donald Fyson, From Iron Bars to Bookshelves: A History of the Morrin Centre (Montreal: Baraka Books, forthcoming).

- Gray, Colleen Allyn. “Captives in Canada, 1744-1763”. M.A., McGill University, 1993. <http://digitool.Library.McGill.CA:80/R/-?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=69625&silo_library=GEN01>

- Holland, Jeanne. “Johnson, Susannah Willard (1729-1810)”. In Cathy N. Davidson and Linda Wagner-Martin (ed), The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995): 448.

- Moussette, Marcel. Le site du Palais de l’intendant à Québec: genèse et structuration d’un lieu urbain. Sillery: Septentrion, 1994.

- Ott-Kimmel, Amy Kristen. “‘A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Johnson’: An Edition”. Ph.D., University of Delaware, 2001.

- Saunderson, Henry H. History of Charlestown, New-Hampshire, the Old No. 4. Claremont: Claremont Manufacturing Co., 1876. <https://archive.org/details/historyofcharles00saun_0>